Publicado el 2022

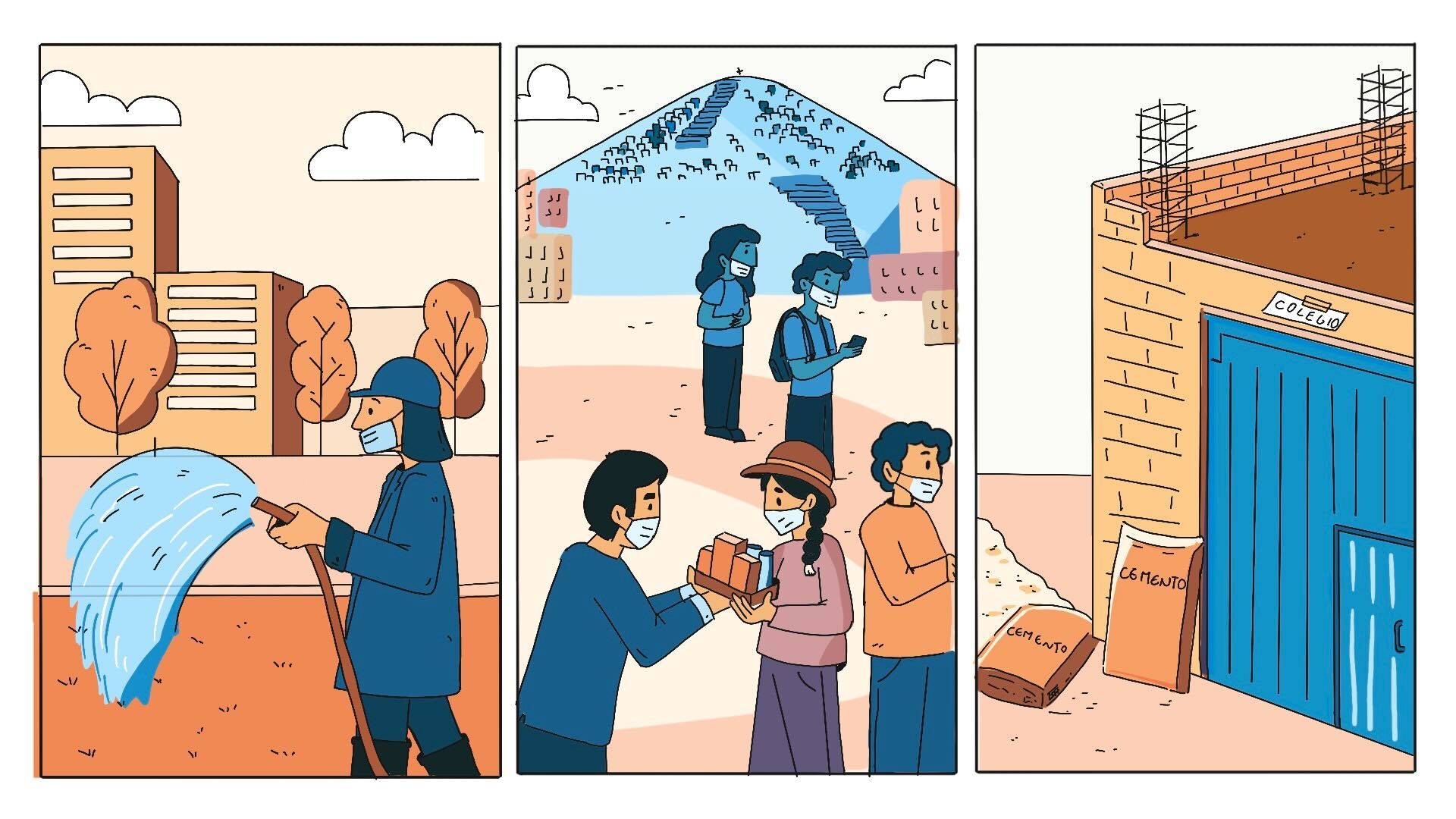

The public accounts of sixty Latin American municipalities reveal inequalities in the spending priorities during the Covid-19 health crisis, according to an investigation by the Latin American Journalists' Network for Transparency and Anti-Corruption (Red Palta). While the poorest municipalities prioritized financial support and food baskets, some of the richer governments allocated a high proportion of their budget to the upkeep of green spaces, treatment of solid waste and sporting activities. Although some resources were redeployed to tackle the pandemic, very often these were insignificant. The investigative team also unearthed cases of direct procurement of public works and failures on the delivery of those works.

By Milagros Berríos, Gianfranco Huamán, Dalila Sarabia, Ignacia Velasco, Javier Revetria, Natalia Arbeláez and Isaías Morales.

The only preschool in La Peñita has no children. There is only a mother, a father and two teachers walking in what should be classrooms, in temperatures in the high 80s. In the stifling heat, they dodge the iron bars, cake their shoes with mud, breathe in the dust. Rather than being filled with children, this concrete structure, located in the northern Peruvian region of Piura on the border with Ecuador, resembles a storage facility for construction materials. Instead of folders and books, there are wheelbarrows, hard hats, wooden ladders, and orange pants once worn by a long-gone civil construction worker. Look around and everything in this place paints a picture of an abandoned project.

The contract to rebuild preschool no. 470 in La Peñita was signed on October 5, 2020, right in the middle of the two deadliest waves of Covid-19. The school was supposed to have been completed in March 2021 but now, two years on, the work has come to a standstill. It is the same story in two other schools in Tambogrande, one of the five urban districts with the lowest Human Development Index (HDI) in Peru.

A total of $2.5 million (9.3 million soles) was earmarked for these three schools, which lie unfinished and gathering dust. But less than half of that amount ($1.2 million) has been spent. Despite being delayed by recent heavy rainfall, classes are set to resume but nearly 300 children, most of them children of farmers and mango and lemon growers, have nowhere to study.

"The previous school was located right here. There was a nice little roof, platform, bathrooms. The school was over thirty years old. Now, in the other places available to us, there is no space for recreation, no games, no sports facilities. Children take their recess inside the classroom. The parents regret having agreed to the construction work," says Lourdes Chiroque, principal of school no. 470, as she seeks some shade amongst the unfinished walls. Last year, with construction at a standstill, the school's 184 pupils, aged between 3 and 5, had to be split up and relocated in two community spaces, in three municipal buildings measuring barely 40 square meters and in the rented house belonging to a neighbor.

In Tambogrande alone, there are 19 other state schools still under construction and unable to be used by over 2,000 children at the start of this school year, the Local Education Management Unit (UGEL) told OjoPúblico.

Wilmer Villegas, 32, a mototaxi driver and vegetable seller from La Peñita, studied at the school where his five-year-old son Lyane still cannot attend classes. "Back in my day, there were classrooms and a field. We'd come to school and have fun. But, for my son, the situation's not like that. How nice it would be if he could come and play," says the treasurer of the Parents' Association (Apafa), flanked by the two mothers and two teachers in the concrete structure that was supposed to cost more than $955,000 and is now left half complete.

"Smile, you are in Tambogrande", says the welcome message to a district that suffered the devastating effects of El Niño Costero in 2017. Between January 2019 and December 2022, the municipality allocated most of its resources to education: $32 million alone for the rebuilding and renovation of 75 schools. One of them, La Peñita, finally got the budget in 2020. But this coincided with one of the world's most serious health crises.

In October 2020, while this municipality, one of the poorest in the country, was coping with the impact of the pandemic and trying to launch projects for its schools, the situation was very different in Lima. The La Molina district, one of the wealthiest in Peru, signed ten contracts for more than $5.5 million over the space of just five days. But these contracts were not for education. No, they were to improve the upkeep of parks and gardens in the district.

The type of contracts and nature of public spending in the richest and poorest districts in Latin America exposes the enormous inequality and differing priorities across the continent. What is happening in Peru is mirrored in other countries such as Chile, where the poorest municipalities focused their attention on social spending such as buying food baskets, while some of the richer ones were able to diversify and allocate resources towards recreational activities.

The Latin American Journalists' Network for Transparency and Anti-Corruption (Red Palta) team analyzed the budgets and allocation of resources in the 30 poorest* and 30 richest urban districts in Peru, Colombia, Uruguay, Chile, Mexico and Guatemala between 2019 and 2022, and identified stark differences in spending during the health crisis.

The team's research revealed that poor municipalities in countries such as Mexico, Chile and Colombia prioritized social spending, using their resources to buy food baskets or to provide financial support to help meet the needs of residents affected by Covid-19 restrictions. Meanwhile, a number of wealthy municipalities were allocating a high proportion of their budget towards sporting activities, garbage collection or infrastructure works for their own assets.

Figures verified by OjoPúblico (Peru), Animal Político (Mexico), La Silla Vacía (Colombia), La Bot (Chile), Ojoconmipisto (Guatemala) and La Diaria (Uruguay) show that although resources were redirected to the purchase of biosafety equipment, oxygen plants or disinfection of public spaces during the public health emergency, many of these cases were insignificant in countries such as Colombia, Peru, Guatemala and Uruguay.

The situation was exacerbated at this time by the indiscriminate use of direct procurement (i.e. no competition) justified by the health emergency declared across all countries. This paved the way for procurement irregularities, alleged acts of corruption that are now being investigated, and failures on the delivery of public works. This is exactly what happened with the three preschools in Tambogrande, one of Peru's poorest districts.

Of the sixty municipalities analyzed by Red Palta, the two with the highest income per capita in 2022 are the very same two with the lowest death rate per 10,000 inhabitants from the new coronavirus: San Pedro Garza García in Mexico and Vitacura in Chile. In contrast, the areas most affected by Covid-19 include five less developed or poorer municipalities which also happen to be situated in Mexico and Chile as well as in Peru. And yet there are others in this latter group that have low recorded levels of deaths.

In Chile, between 2019 and 2022, the five richest and five poorest municipalities spent more than 533 billion Chilean pesos ($670,219,102) on public procurement. The richest spent 83 billion Chilean pesos (€104,894,567) more than the poorest, which is equivalent to 37% more.

Three of the five poorest municipalities saw their greatest expenditure in the year 2020, compared with the other years analyzed. This increase is not just related to Covid-19 because some of the municipalities also spent heavily in areas such as the upkeep of green spaces or the building of a sports center, as well as other recurrent services such as garbage collection.

But when it analyzed purchases by category, LaBot identified enormous pandemic-related social expenditure: some municipalities spent millions on buying food baskets to meet the needs of their residents.

For example, in the municipality of Cerro Navia, which had the highest Covid-19 death rate (64 per 10,000 inhabitants) among the municipalities analyzed in Chile, a preliminary review shows that social spending increased more than eightfold as a result of the direct procurement of nearly 20,000 food boxes when the pandemic affected mobility and income for its residents.

In some of Chile's wealthier areas, a greater proportion of social spending went on recreational uses such as buying equipment for sporting activities. The highest level of spending in these municipalities comes in the year 2022. One of the municipalities spent four times more than the previous year, while three others spent twice as much and, in one municipality, the level of spending was similar to previous years.

In 2022, the budget expenditure per capita in Vitacura, one of Chile's wealthiest districts, was €1,658. Meanwhile, for Conchalí it was just €381.

In Mexico, during 2020, at a time when the virus was spreading rapidly and before the first vaccines had arrived in the country, the five poorest urban municipalities reallocated their budget to social support measures such as electronic transfers and vouchers (payments in kind that can be exchanged for food or other products) in order to help people deal with the pandemic.

The research carried out by Animal Político identified that in León, Guanajuato State, the municipality with the highest number of people living in multidimensional poverty (816,934), the resources allocated to social support and public works, such as parks, markets and squares, doubled in 2020. Social support spending increased by 55% from $3,682,503 to $5,735,086 (based on the exchange rate for that year). As regards spending on public works, the increase was slightly more than double, rising from €25,322,010 to €53,286,784.

"Because of the pandemic, we have allocated public resources to preventing the spread of the virus, but also to support those most affected by the consequences of the disease," said the government of León, Guanajuato State.

A similar situation occurred in the other four poorest municipalities in Mexico, which up to last February recorded more than 333,000 victims of Covid-19. For example, in 2020, Ecatepec, Mexico State, increased its spending on contracts to provide social support.

One of these initiatives was the Ehécatl Plan, consisting of 30 actions to support the population during the Covid-19 pandemic, including the distribution of basic family packages. Resources were also allocated towards the purchase of 300,000 hygiene kits, for which over 75 million Mexican pesos ($3.5 million) were redirected.

The borough of Iztapalapa, the most populous in Mexico City, provided funeral support to local families and launched the social initiative Market, Community, Food and Supply (Mercomuna) handing out vouchers for 350 pesos (equivalent to less than 20 dollars) to be spent with local businesses on basic necessities.

In contrast to this situation, the two richest municipalities - Benito Juárez, in Mexico City, and San Pedro Garza García, in Nuevo León - cut the budget for financial support and carried out public works such as resurfacing of roads and sidewalks, upkeep of public parks and adaptation of pedestrian crossings.

The Benito Juárez borough of Mexico City prioritized the improvement of public markets and the buying of sports, electronic and radio communication equipment and even vehicles for cultural centers as part of its social budget.

In Colombia, an analysis of the ten urban municipalities with the highest and lowest levels of multidimensional poverty (according to 2022 forecasts) revealed that none had a significant number of contracts associated with Covid-19.

In 2021, only Maicao and Tumaco, two of the poorest districts, signed more contracts for disinfecting public spaces, town halls or schools and for buying biosafety equipment and food packages for the most vulnerable. Both recorded the highest fatality rates (percentage of deaths among positive cases) for the virus among the municipalities analyzed.

Meanwhile, it was observed that the municipalities with less poverty, such as Funza or Sabaneta, procured more complex services such as adaptation of intensive care wards or for tracking positive cases in homes. Their Covid-19 fatality rates were lower than those of Maicao and Tumaco.

If spending on public services is considered, there is a marked difference between the poorer municipalities, which are still dealing with the lack of basic services such as water, and the richer ones. This is because the water and sewerage infrastructure does not yet cover the whole municipality or the water supply is intermittent. The same is true for electricity and garbage disposal.

In those districts with the highest multidimensional poverty, such as Maicao or Villanueva on the Caribbean coast or Tumaco on the Pacific coast, most of the contracts for public services during the four years analyzed were for the supply of water in tankers, and for the construction of a rural aqueduct or the extension of the network to certain neighborhoods. In Clemencia Bolivar (Caribbean region), the largest contract in 2019 was for sewerage networks (1.2 billion Colombian pesos, equivalent to €251,586).

As regards social spending, over the period analyzed, most contracts in the richest municipalities were for centers used to look after children aged 0-6 years (early childhood), the elderly, people with disabilities and their carers, as well as mothers.

Specifically, in Cajicá, in two of the four years examined, its largest contracts were for programs aimed at people with disabilities (2020) and for the construction of a child development center (2022).

Meanwhile, in the municipality of Envigado, in the department of Antioquia (Andean region), one of the poorest areas, the largest amount spent in 2021 on social expenditure was almost 17 billion Colombian pesos (over €3.5 million) to promote sport.

Unlike in other countries, in Uruguay there is no large gap between type of spending in the richest and poorest municipalities. The departmental intendancies, with the exception of the capital Montevideo, did not allocate significant resources to ease the effects of the pandemic.

The Intendancy of Montevideo increased health spending from $13 million in 2019 to $17 million in 2022. Most of this was allocated to the care system (polyclinics).

Spending on social policies also increased from $5 million in 2019 to $16 million in 2021. The bulk of this increase was due to the launch of the ABC Plan (Apoyo Básico a la Ciudadanía), a citizen support program built around the creation of temporary jobs and health care in the context of the health crisis.

La Diaria also discovered that in Artigas, Rivera and Cerro Largo, three of the departments most affected by Covid-19, spending between 2020 and 2021 (excluding operating costs) was almost exclusively on heavy machinery.

And, just like what happened in other countries in the region, in Uruguay the most significant resources to combat the effects of the pandemic came from the central government via the Covid Fund. Under this program, the intendancies allocated a total of 15,000 jobs from the national government's "Solidarity Days" (Jornales Solidarios) program to those unemployed who were not receiving any other social benefits from the State.

In Peru, which has one of the highest mortality rates from the new coronavirus in the world, health spending was not a priority in recent years for the ten districts analyzed. The five poorest, including Tambogrande, allocated only 3% ($6 million) while the five richest allocated just 0.91% ($2.8 million) to health spending.

Of this total, the municipalities with the lowest HDI spent $475,624 on the pandemic response while those with the highest HDI spent just $112,000, less than a quarter of that figure. The Peruvian Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) does not give precise details about how the resources that come under "Prevention, control and treatment of Covid-19" were used.

What does become clear when looking at public spending during the health crisis is that there are certain large-scale infrastructure or investment projects which, two years on, no longer meet the needs of the people. For example, in 2021, the municipality of Tambogrande procured an oxygen facility so that it could supply oxygen to the local residents.

A few meters from that facility, speaking at the entrance to the Carlos Schaefer Maternal and Child Health Center in Tambogrande, its former director Ricardo Remicio recalls that the system collapsed in the first two waves of Covid-19 but now, after the fifth wave, there is no longer a high level of demand from infected patients. "At that time, we had no oxygen. Now we have plenty. We now have a production facility with more than 100 balloons," said the doctor one week before leaving his post.

In Tambogrande, the virus emerged in the urban area and spread to its more than 180 population centers, where the local people source water from canals, rivers and wells and carry it home by donkey. In schools, such as La Peñita, parents need to buy drinking water for their children.

While the priority during the pandemic was on health care, in countries such as Peru, Mexico, Uruguay and Colombia, responsibility for this fell mainly on the shoulders of the central or regional government or, in some cases, on the state and federal government.

"Local budgets are tiny and there's not much you can do [about health during the pandemic] with them. Clearly, it's all about the central government. Another important issue is the vast differences in the distribution of the budget. Local governments have minimal involvement with their own resources. In many cases, income is a percentage of the General Sales Tax (IGV) and depends on how much is consumed. So the poorest are going to end up receiving less than the richest," says Carlos de los Ríos, an economist at the Peruvian headquarters of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), which created the HDI indicator.

For Catherine Eyzaguirre, an economist specializing in human development at Oxfam Peru, the different spending priorities of local governments during the pandemic are shaped by the role of the public sector in the various socio-economic situations in Latin America. "The idea of privatizing access to rights has meant that many people are turning to the private sector to meet their health, education and transport demands. In middle-class districts, such as certain areas in Lima, most people do this. They don't require any support from their municipality. Perhaps what they're more concerned with are green spaces, public safety, more patrols," says Eyzaguirre, who is also Oxfam Peru's economic justice projects officer.

In contrast, she adds, in districts where there is a greater demand for public services, precisely because the local people are unable to pay for those services themselves, there is pressure from the community to receive some kind of support from the local authorities. "What happened in the pandemic is a prime example: wealthy families could afford a medical appointment and could stock up at the supermarket, but lower-income households required support measures, vouchers. They demanded more from the public purse," she says.

During the pandemic, when the state of emergency was declared, governments turned to direct procurement and contracts.

Between 2020 and 2022, 3,510 contracts were awarded in Guatemala, of which 2,584 went to the five richest urban municipalities and 926 to the other five poorest. The former represented a total of 1,327,446,073 quetzales ($170,093,517) whereas the latter received 457,394,090 quetzales ($58,603,996).

The most frequent purchase among the ten municipalities analyzed was construction (47% of contracts). The poorest municipalities concentrated more on fixing their streets, leasing water, and on building and repairing facilities in existing public buildings.

In contrast, wealthier municipalities focused on improving basic services such as garbage collection, electricity and street lighting. The most prominent works involved buying materials separately and constructing all kinds of new buildings as well as acquiring new transport facilities.

Procurement in relation to health and cleaning supplies was less important. San Andrés Itzapa, in the department of Chimaltenango, is one of the poorest districts, with a Covid-19 death rate of 60 per 100,000 inhabitants. Here the authorities directed 56 of their 84 purchases over three years toward street improvements.

Between 2019 and 2022, in Colombia, where the team's analysis was based on the performance of each borough using its own resources, 72% of the contracts concluded by the municipalities with the highest and lowest multidimensional poverty were direct procurement contracts.

All the municipalities analyzed have plenty of contracts for the operation of state agencies but, in the case of the least poor ones, the contracts are a little more diverse in terms of their distribution. So as well as spending on stationery, cars, equipment and cleaning, they also invest in public infrastructure, education, social and cultural programs as well as science and technology initiatives.

Meanwhile, the poorest municipalities have lots of contracts for maintaining bureaucracy and for minor works but fewer contracts for other categories. In the case of Maicao, a municipality in the northern department of La Guajira (Caribbean coast), which has a multidimensional poverty index of 60%, around 21% of contracts in 2021 were for administrative matters such as life insurance for civil servants, security for the mayor, air conditioning equipment, refrigerators and furniture for offices.

In Peru, between 2019 and 2022, children would climb trees or go up into the hills to get a signal and take part in virtual classes. Others, such as Lyane, the son of mototaxi driver Wilmer Villegas, returned to face-to-face classes in municipal spaces or rented houses.

OjoPúblico's analysis of the budgets of the municipalities with the lowest Human Development Index shows that Tambogrande, La Arena, La Unión, all in the Piura region, as well as Pichanaqui and Perené, in the Junin jungle, allocated the highest percentage of their resources (27%) to education, including infrastructure, furniture and training.

In contrast to the priorities of the poorest districts, the municipalities with the highest HDI in Peru, namely La Molina, Jesús María, Lince, Magdalena and Pueblo Libre, all located in the capital city Lima, spent more on planning and management (33%), environment (26%, including garbage collection and green spaces), public order and security (15%), and housing and human development (8%).

Between 2019 and 2022, the five poorest urban municipalities had a total budget (amended initial budget) of $331,283,437, while the budget for the five richest was 42% higher at $472,283,150. Of those figures, while the five poorest spent over $61,407,351 million on education, the rich spent just $131,775 (0.03%).

UNDP economist Carlos de los Ríos stresses that there is enormous inequality in the distribution of the per capita budget in the districts and that there is no correlation between the HDI of these localities and State presence. "You'd think that if there were places with a worse HDI or more poverty, more money would be injected there because that's where more public assets are needed to lift people out of poverty. Roads, health and so on. But that's not the case. There's no correlation," he says.

De los Ríos, who makes this analysis on the basis of national figures, adds that this inefficiency of public spending to translate into improved HDI may be mirrored in several countries in the region. But he also points out that there may be cases where district municipalities that have allocated resources, for example, towards green spaces or garbage collection, have suddenly done so because the central government had earmarked money for products such as food baskets. "The mayor sees the whole source of income. He's a key factor in decision-making. If you look at it as national spending, at the local level, you should find significant spending on productive things," he says.

In Colombia's neighbor, the municipalities with the highest multidimensional poverty signed contracts for child meals, adaptation or maintenance of schools, school transport, as well as preparation for higher education entrance exams.

Meanwhile, those with less poverty do more than simply cover basic needs, offering programs for learning English, complementary workshops (including, in the municipality of Cajicá, a robotics workshop) and life planning activities, as in the municipality of Funza. For example, in Funza and in Sabaneta, there is a contract to build an innovation and technology center right in the midst of a health crisis.

In Chile, the municipalities also spent money on education in the period under analysis. The largest contracts correspond to poor municipalities, which prioritized conservation and improvement works in kindergartens and schools, some of which took place at the height of the pandemic. The municipality of La Pintana was the one that spent the most in this area, procuring services to upgrade the electrical wiring in some of its schools.

Spending in some of the richer municipalities involved the procurement of laptops and transport services for school activities. Vitacura, one of the more prosperous municipalities, even entered into a contract for an assessment service to measure how well students were progressing in their learning in a number of municipal schools.

In Peru, the Tambogrande district produces mangoes, lemons and grapes but has no drinking water for its 122,000 inhabitants. In 2002, a referendum on whether to allow mining operations in the region resulted in an overwhelming rejection of the proposals and the mining company was forced to end its operations. In 2017, the area was battered by rains and floods as a result of El Niño Costero.

Between 2019 and 2022, the district municipality allocated 40% of its resources to education infrastructure. An OjoPúblico team visited schools that were set to be rebuilt in this district, situated 1,000 kilometers from Lima, and found various cases where the contract date for the delivery of the works had not been met. These include the three schools La Peñita (470), Ayar Uchu (481) and San Fernando Olivares (907) where works being carried out by the district municipality are now at a standstill. "As you can see, the building work for this facility started in September 2020. The first stone was laid with great enthusiasm and joy. We were told it would be complete in March 2021. The pandemic was already in full swing at that time and there were so many things happening. And, just like that, the work stopped. There was nothing luxurious about the school but it made lots of children happy," says Elizabeth Aguilar, principal of the Ayar Uchu preschool, where the parents had to ask to use a municipal space and rent premises from local residents.

At the Town Hall, Segundo Meléndez, mayor of Tambogrande, argues that the blame lies with the contractor firms as well as with previous administrations, which he accuses of accepting unfinished works. "It's not just a management issue, it's a national problem. The State has resources and allocates them, but it is the institutions, ministries, local and regional governments and the people themselves, who have become accustomed to doing things wrongly. Now everything is tangled up in traps and bureaucracy," he says in his second month in office.

Two of the three stalled projects under the municipality's responsibility had the same contractor: JF Proyectos y Construcciones SAC, which has not been disqualified by the State Procurement Supervisory Body (OSCE).

Other companies experiencing delays have lamented the economic difficulties resulting from the pandemic. "Costs have changed. The cost of cement has gone up. In the tender documents, the cost is 19 soles ($4) but the market price is now 22 soles (€5.80). Rising costs have caused cash flow problems," says a worker who prefers not to be named, responsible for the works at the Nuestra Señora de Fátima school (14140) in Tambogrande. This school should have been ready last January and is now 53% financially complete.

Failures on the delivery of public works, as well as the shortcomings identified by this journalistic team, have been acknowledged by the Local Education Management Unit in Tambogrande, by the district mayor and, in certain cases, by the General Comptroller of the Republic of Peru.

The team's analysis of social spending in Latin America confirms that there are rich districts that invested in public services such as garbage collection or sporting activities, while the poorest ones invested in basic rights such as education, although not all of them fully performed their contracts.

Of the areas analyzed in this research, the Central American country of Guatemala was also identified as having the districts with the lowest per capita public spending in 2022: Cobán and Jalapa, both considered poor areas. On the other side of the border, Mexico has the district with the highest per capita income: San Pedro Garza García, considered to be one of the wealthiest. So, while public sending for a resident of San Pedro Garza García was $1,666 last year, for a resident of Jalapa, this was just €65. When Covid-19 hit the region, the Peruvian President Martin Vizcarra, subsequently involved in the Vacunagate scandal, said that the virus was "entirely democratic", alluding to the fact that anyone, regardless of their socio-economic conditions, could become infected. Wilmer Villegas, from La Peñita, does not agree. While his neighbors in the richer districts stayed at home and washed their hands to avoid being infected, he had to get a special permit to work in the city and collect water from the river canals to wash himself. His uncle and aunt became infected and died. His child did not learn how to study from a mobile phone. Wilmer, his face tanned, leans wearily against one of the walls of the school that is yet to be rebuilt. And just breathes in the dust. In Latin America, the pandemic is moving on but inequalities remain.

For this journalistic investigation by the Latin American Journalists' Network for Transparency and Anti-Corruption (Red Palta), carried out by OjoPúblico (Peru), La Bot (Chile), Animal Político (Mexico), La Diaria (Uruguay), Ojo con mi Pisto (Guatemala) and La Silla Vacía (Colombia), the five poorest and five least poor (richest) districts in the six Latin American countries were identified.

The investigation set out to analyze public spending and contracts in those 60 municipalities in Peru, Colombia, Uruguay, Chile, Mexico and Guatemala, between 2019 and 2022.

One of the challenges in locating the poorest and richest districts was identifying similar types of measurement because not all countries had the same type of methodological indicators.

For example, to classify districts or municipalities as poor or rich, reference was made in Peru and Uruguay to the 2019 Human Development Index (HDI) (the latest available report) whereas, in Guatemala, the 2018 HDI (the latest available report) was used. In the case of Chile, Colombia and Mexico, multidimensional poverty figures were used because they did not have HDI reports.

For both indicators, the smallest sub-national political unit, such as district or municipality, was analyzed. However, in those countries where this was not possible, the team used the information available in each case, such as at regional or provincial level only. The localities analyzed are either urban or have an urban presence.

To calculate the Covid-19 death rate, the team gathered official figures on deaths from the disease, from the start of the pandemic until December 2022, and population figures were gathered according to the latest census conducted in each territory.

In order to standardize the budget in US dollars, the team used the annual average exchange rate of each local currency to the US dollar prepared by the World Bank in the case of Mexico. For all the other countries, the exchange rate at the time of going to press was used.

Editing and coordination of Latin American reporting: Nelly Luna Amancio (OjoPúblico) Journalistic research: Milagros Berríos and Gianfranco Huamán (OjoPúblico), Dalila Sarabia (Animal Político), Ignacia Velasco (La Bot), Javier Revetria (La Diaria), Natalia Arbeláez (La Silla Vacía) and Isaías Morales (Ojo con mi Pisto). Drafting and data analysis: Milagros Berríos and Gianfranco Huamán (OjoPúblico) Country publishers: Francisca Skoknic (Chile), Ana Carolina Alpírez (Guatemala), Mauricio Torres (Animal Político), Juanita León (La Silla Vacía), Natalia Uval (La Diaria). Illustrations: Claudia Calderón (OjoPúblico) Social media: Isaías Morales (Ojo con mi pisto).

A project by: Red Avocado

With the support of: Open Contracting Partnership

Conoce los reportajes relacionados con esta investigación

Contactanos